You can prevent osteoporosis by avoiding certain risk factors

|

Osteoporosis (“porous bones”) is a silent condition in which bones become less dense and more likely to fracture. It’s a major health threat for an estimated 10 million Americans with the disease and 34 million Americans with low bone mass.

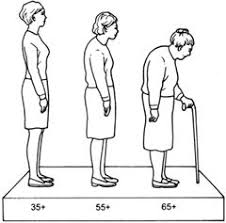

Often called a pediatric disease with geriatric consequences, bone density decreases partly because hormone levels (such as estrogen and testosterone) decrease as people age. Estrogen, the main female hormone, helps prevent bone from being broken down and therefore helps to keep it dense and strong. Testosterone, the main male hormone, stimulates bone formation.

Older women are affected by the decrease in hormone levels more dramatically than older men. At menopause, the decrease in bone density speeds up dramatically as estrogen levels nosedive. During the first few years after menopause, bone density may decrease by as much as 5 percent each year. After that, it decreases by up to to 2 percent each year.

Also, on average, women usually have lower bone density than men to begin with. Thus, women are more likely than men to develop osteoporosis.

As men age, testosterone levels decrease slowly. Men produce small amounts of estrogen. Men with low testosterone or low estrogen levels are more likely to develop osteoporosis.

The bones in the wrist, hip and spine are most often affected by osteoporosis. Close to one out of five hip fracture patients ends up in a nursing home and only one out of two regain their independence.

Common risk factors for developing osteoporosis include:

• Having a small frame. Thin people tend to have less dense bones than heavier people. Part of the reason is that body weight puts stress on bone, stimulating it to form more bone. Also, thin women may have less body fat and lower estrogen levels than heavier women.

• Family history of osteoporosis. If you have close relatives with osteoporosis, you’re more likely to develop it. The risk of developing osteoporosis is even higher when a relative has had a fracture as a result of osteoporosis.

• Menopausal or post-menopausal. During and after menopause, declining estrogen slows bone construction and causes less absorption of calcium by the kidneys and intestines. Each year during menopause, about 3 percent of bone is lost from the spine and 1 percent from arms, hips, and other sites. Bone loss slows down to about 1 percent per year 4 years after menopause.

• Certain medications. Long-term use of corticosteriods to treat asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s Disease and other inflammatory conditions can contribute to lower bone mass. Anticonvulsants, thyroid medications, immunosuppressants given after organ transplant, chemotherapy, aromatase inhibitors, diuretics and blood thinners such as heparin can contribute to bone loss.

• Low-calcium diet. Those who do not consume enough calcium or who have vitamin D deficiency throughout their lifetime are more likely to develop osteoporosis. A negative balance of only 50-100 mg of calcium per day over a long period of time is sufficient to produce osteoporosis.

• Lack of exercise. Bone is formed in response to weight-bearing activity. Those who are less physically active throughout life are more likely to develop osteoporosis.

• Smoking. Cigarette smoking increases risk because it interferes with the re-formation of bone.

Bones are not static. They are always being broken down and rebuilt. This process depends on a delicate balance of nutrients. Bone loss is unavoidable but it can be slowed down with calcium intake and exercise. Perhaps even more important than the amount of calcium ingested is the amount excreted as a result of calcium drainers in our diet.

Major calcium drainers include:

• Caffeine: Caffeine is a powerful diuretic, causing the kidneys to increase calcium excretion. The more regular coffee you drink, the more calcium is excreted in your urine. The loss amounts to about five milligrams of calcium for every six ounces of coffee or two cans of cola.

• Soft drinks: Carbonated soft drinks (sometimes nicknamed “osteoporosis in a can”) can promote osteoporosis. The carbonation irritates the stomach by moving calcium — a natural antacid—from the blood into the stomach. The blood, now low on calcium, replenishes its supply from the bones to protect muscular and brain function (both of which heavily depend on calcium). In addition, phosphoric acid in some soft drinks interferes with calcium absorption.

• Excess Protein: Protein promotes urinary calcium excretion. This means that the more protein you eat, the more you will lose calcium via your urine. Protein does not appear to affect people with sufficient intake of calcium, magnesium and vitamin D.

• Sodium: Every 500 mg of sodium causes post-menopausal women to lose an extra 10 mg of calcium. Sodium sources include salt, baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), MSG (monosodium glutamate) and soy sauce.

• Alcohol: Alcohol interferes with the absorption of both calcium and vitamin D, and increases parathyroid hormone levels, which in turn reduces the body’s calcium reserves.

• Stress and depression: Higher cortisol levels, often found in depressed patients, may contribute to bone loss. Cortisol is a corticosteroid. Corticosteroids destroy osteoblasts (bone-building cells).

Your age determines your daily calcium needs:

9-18 years: 1,300 mg

19-50 years: 1,000 mg

Over 50 years: 1,200 mg

Bone is not solely dependent on calcium, however. The best program consists of a cocktail with many minerals and nutrients — for example, magnesium, vitamin D and boron can work together to maintain a strong skeleton. Vitamin D is freely available from sunlight during the warmer months, but fish, milk and some soy beverages provide the vitamin all year round.

The latest nutritional research points to three other important team players — strontium, vitamin K and collagen. Be sure to include mineral-rich foods in your diet daily, including raw nuts, seeds, dark leafy greens, yogurt, broccoli and seaweed (a source of over 60 minerals).

With age, bone loss is inevitable. It is important to note the impact we may have in influencing the health of our bones and the onset and pace of osteoporosis, namely in our choice of minerals, nutrients, medicine, diet and physical activity.

No comments:

Post a Comment